Contents

Tuesday, November 10, 1908

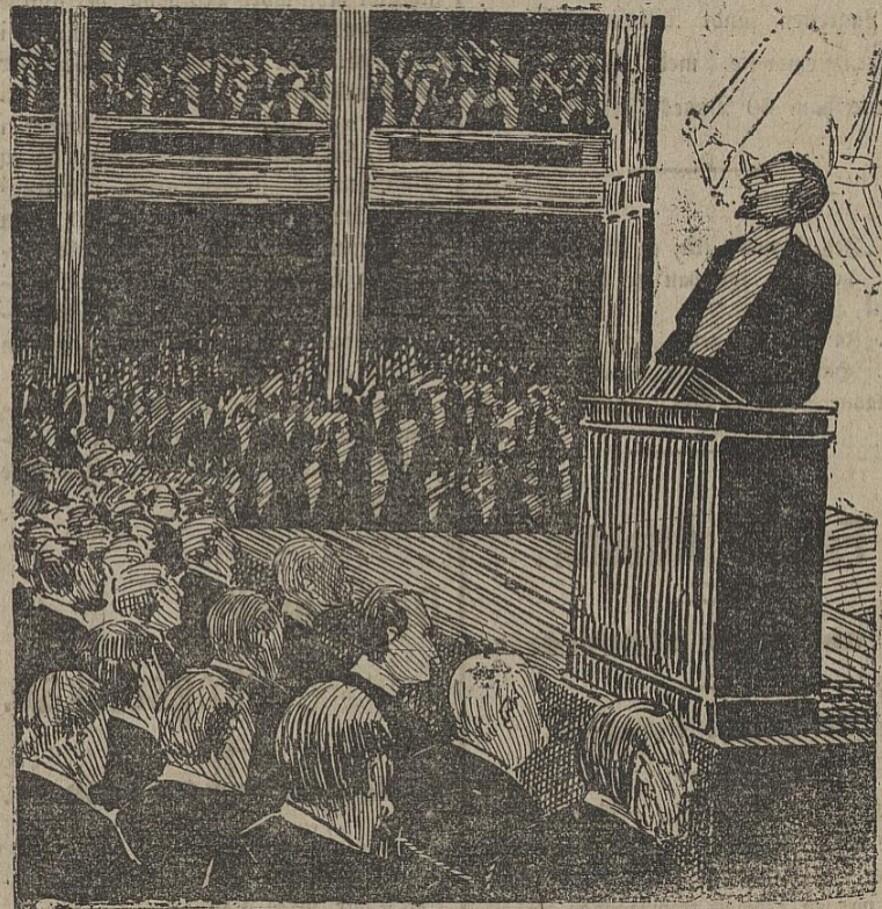

The Norwegian Geographical Society arranges a meeting in the great hall of the Old Lodge in Kristiania.

The room is full.

The King, members of the government, diplomats and scientists, including Fridtjof Nansen - everyone is eagerly waiting to hear the man who is climbing to the podium.

Roald Amundsen is 36 years old. It is two years since he returned from his last expedition and wrote himself into polar history as the conqueror of the Northwest Passage.

Now a new plan will be presented.

In preparation, Amundsen has undergone training in marine research and has been in close contact with both Fridtjof Nansen and the marine scientist Bjørn Helland-Hansen.

The plan to drift across the Arctic Ocean has great scientific potential.

- 1/1

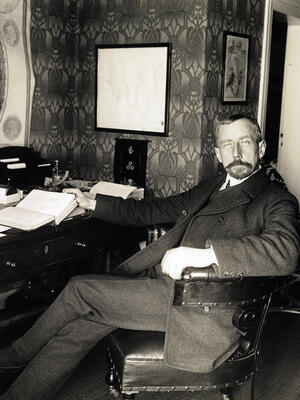

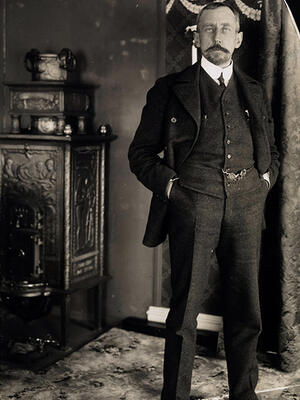

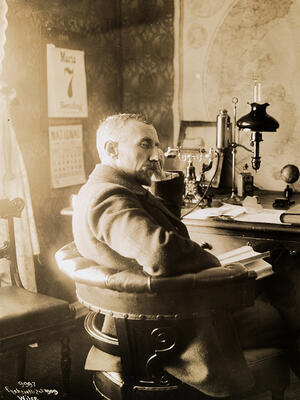

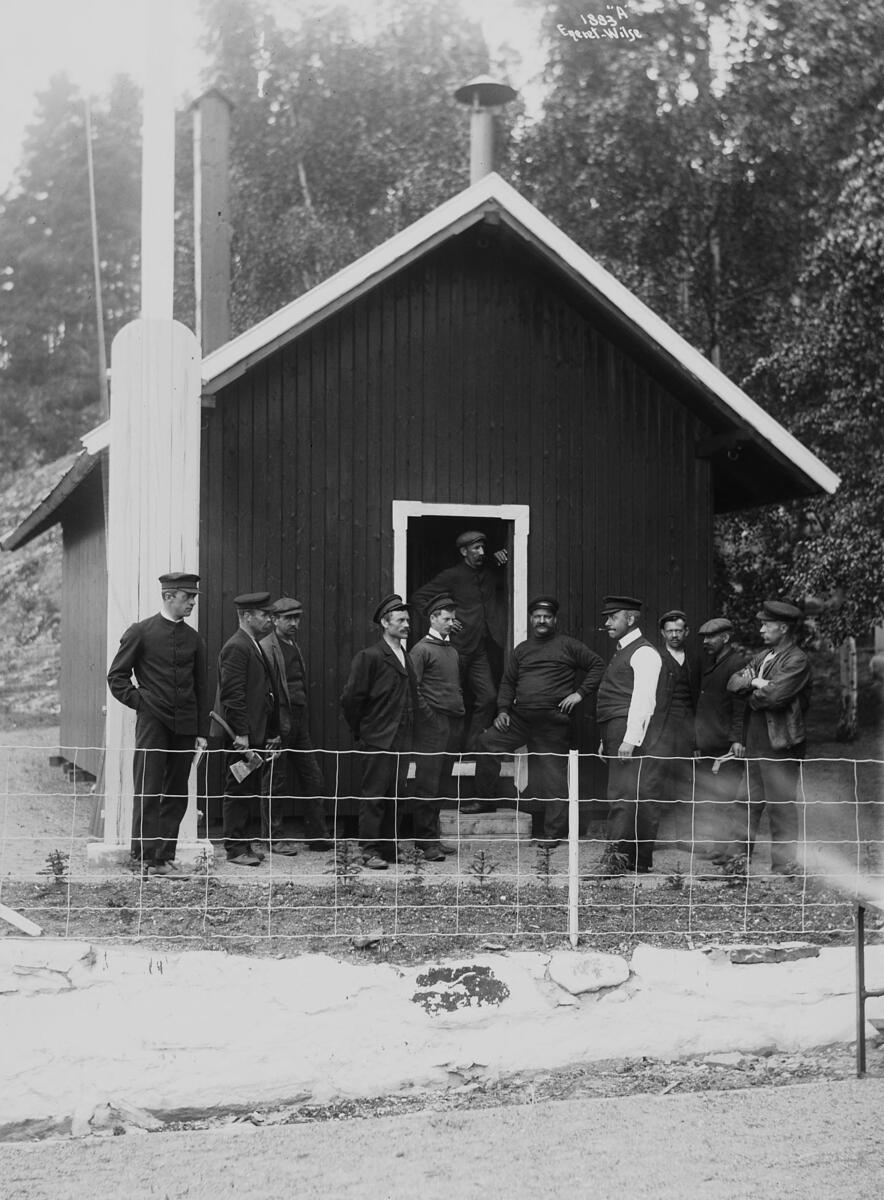

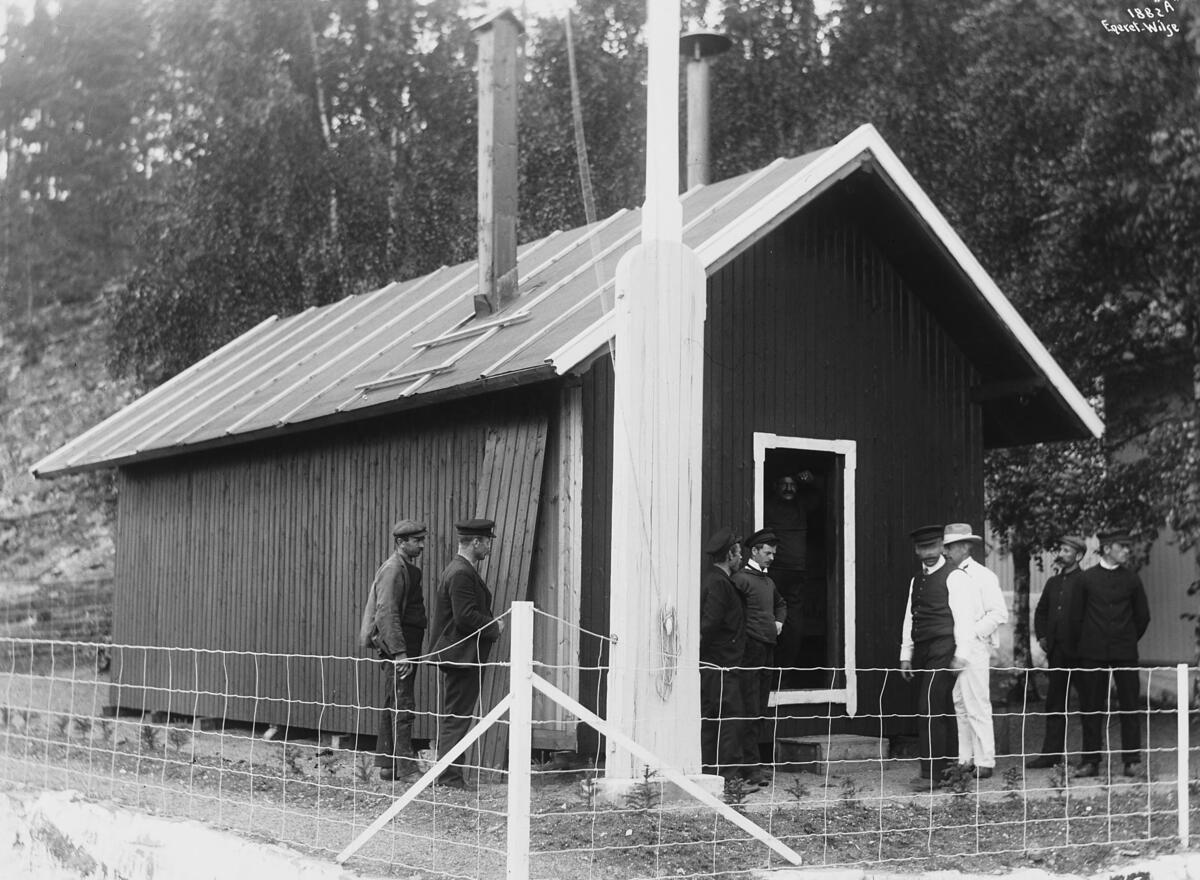

In the summer of 1908, Amundsen goes to Bergen to participate in a "series of marine surveys in the Bergen fjords", the newspapers can report. The stay lasts two months, and in the following spring he is back on a new six-week course. Several of the crew also receive similar training. The teacher is Bjørn Helland-Hansen (right), who becomes an important figure in the expedition preparations. He will also be one of the few people aware of Amundsen’s new plans for the South Pole before departure. Photo: Follo Museum, MiA.

Sunday, March 7, 1909

Photographer Anders Beer Wilse has come to visit Roald Amundsen. Amundsen poses at his desk and by the stove in the living room, and outside in the snow.

- 1/10

- 2/10

- 3/10

- 4/10

- 5/10

- 6/10

- 7/10

- 8/10

- 9/10

- 10/10

Carl Hagenbeck. Phto: Wikimedia Commons

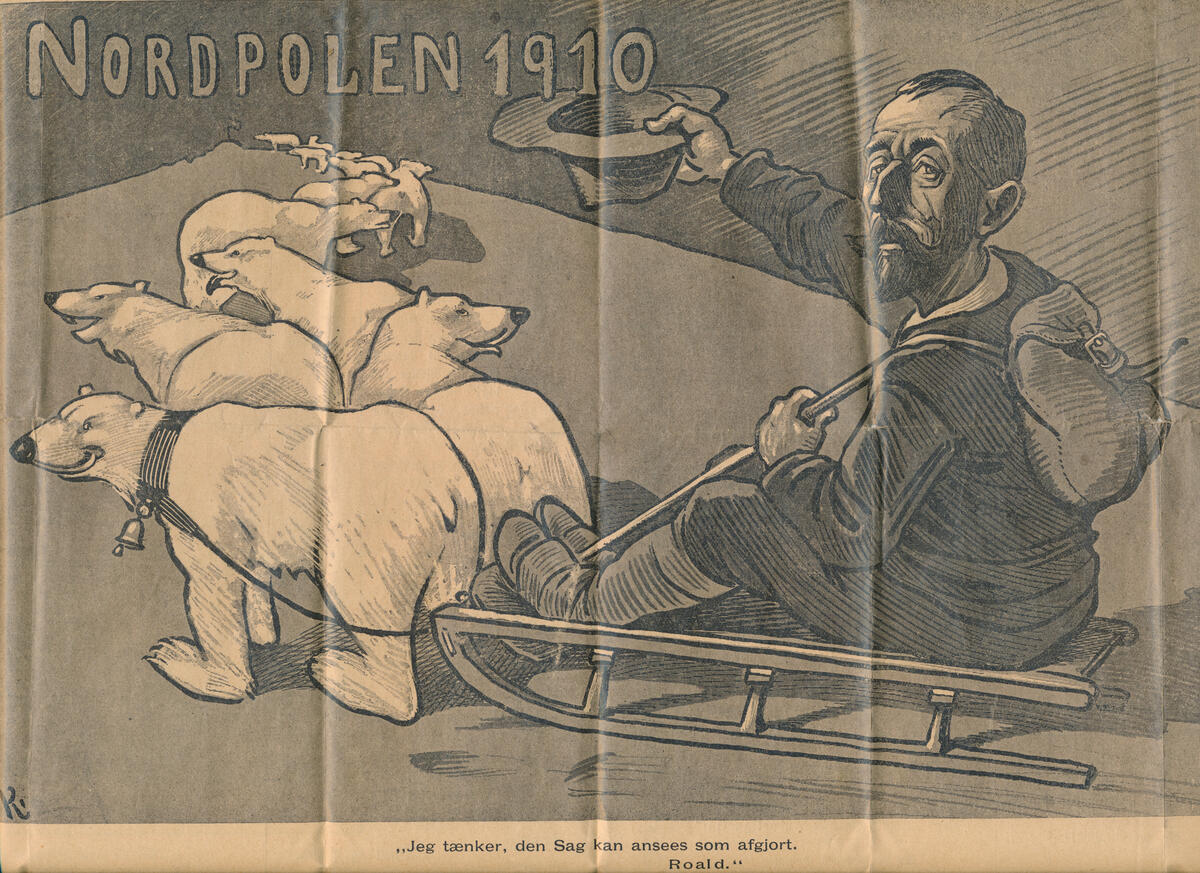

Amundsen has a bold plan

He wants to train polar bears so that they can pull his sledges. The German animal trainer Carl Hagenbeck gets the job.

Hagenbeck is an optimist. He tells journalists that it will also be possible to teach the bears to sleep in tents at night, so that Amundsen and the others can lie next to a soft and warm polar bear every time they camp.

When the newspapers ask Amundsen about the polar bear plan, he replies:

Amundsen experiments not only with draft animals

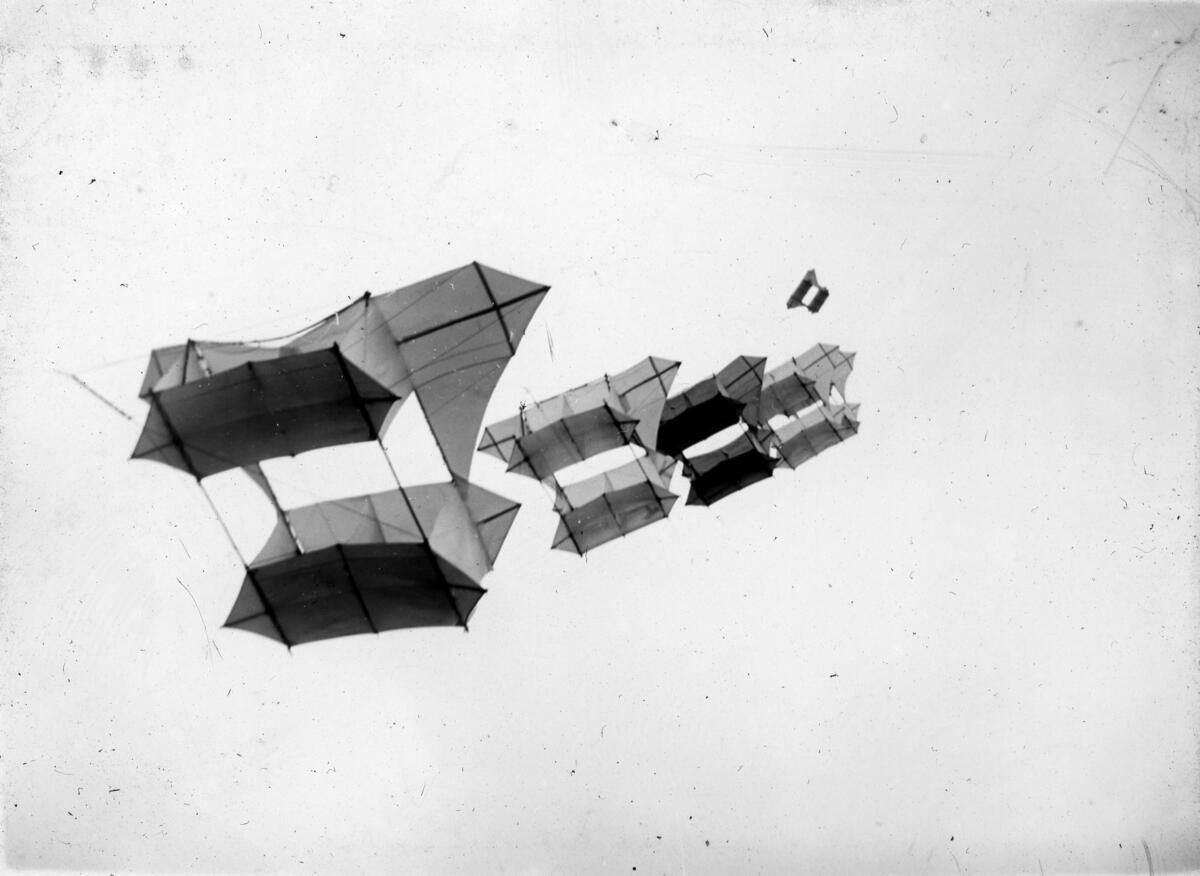

In July 1909, he tests specially made kites near Horten. These can take a human several hundred metres up into the air, which will be useful for reconnaissance on the journey across the Arctic Ocean.

The expedition's deputy leader, Ole Engelstad, describes the equipment to the journalists present:

Thursday, July 22, 1909

Roald Amundsen receives a visit from the expedition's deputy leader Ole Engelstad and marine scientist Bjørn Helland-Hansen.

It will be the last time Amundsen sees Engelstad alive.

Ole Engelstad was intended to have an important role in the expedition and was heavily involved in the preparations. Photo: Follo Museum, MiA

The following day Engelstad goes out to Vealøs off Horten to test fly the kites, together with the aviation pioneer, Einar Sem-Jacobsen.

They send up a kite, fastened to the ground with a long copper wire.

At four o’clock the thunderstorm hits Horten.

Engelstad touches the copper wire that is attached to the kite.

«There's quite a lot of electricity in the air now. I grabbed the cable and got a real shock,» he said to Sem-Jacobsen.

To avoid any greater injury, they decide to let the kite hang in the air until the storm is over.

No one wants to risk a major shock.

But it still happens that Engelstad changes his mind.

He watched the clouds for a while and then began to crank in the kite that was up. A blinding flash suddenly lit up the whole kite string, the winch was enveloped in smoke, and they saw Engelstad collapse.

Lightning strikes his body and exits through his hands and feet. His boots almost burn up and the grass beneath is left charred.

It is over in seconds.

Unconscious, Engelstad falls backwards. There is a burnt smell and smoke comes from the body. People run forward – there is still a pulse – but time is short.

Engelstad is carried aboard a motorboat. But it is in vain.

Ole Engelstad never regains consciousness and is declared dead when he comes ashore.

Engelstad's body is later transported to Porsgrunn where his funeral takes place.

- 1/1

During the South Pole journey, Amundsen named a mountain in Ole Engelstad’s honour. After he returned to Norway in 1912, he also contributed to the erection of a memorial in Engelstad’s hometown of Porsgrunn. Photo: Follo Museum, MiA.

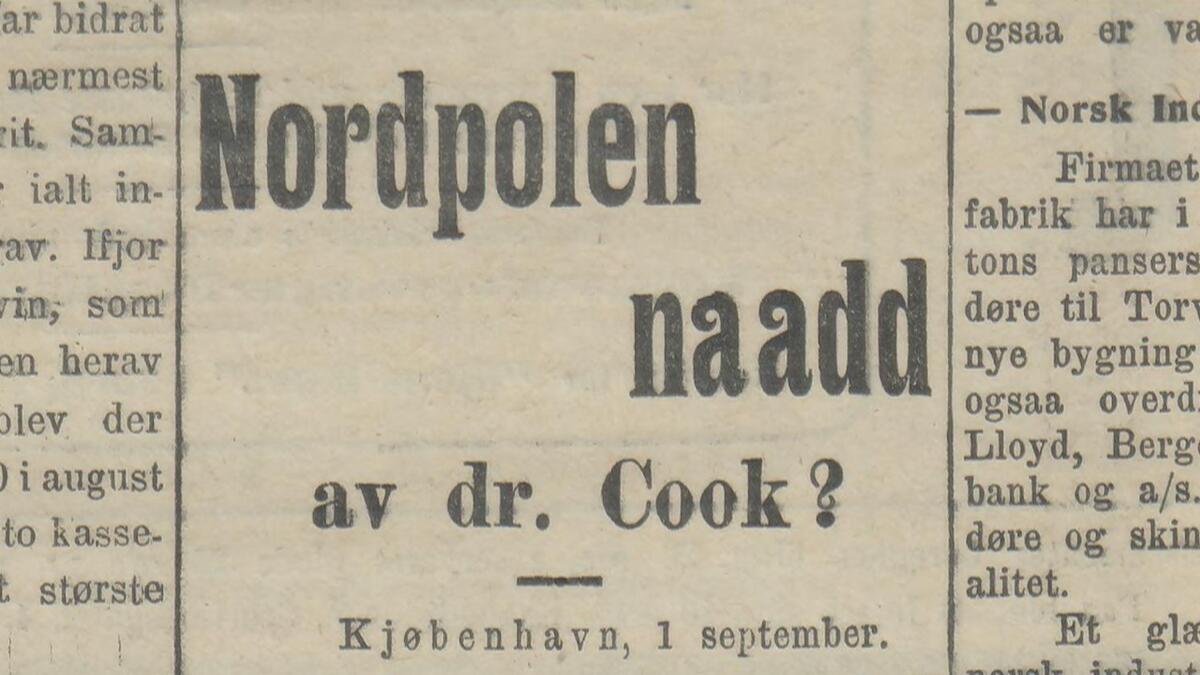

Wednesday, September 1, 1909

The message that turns everything upside down.

«North Pole reached,» write the Norwegian newspapers.

The American Frederick Cook claims that he and his Inuit companions Ittukusuk and Aapila have become the first to reach the North Pole. This is said to have happened on April 21, 1908.

On their way home from the Pole, they have overwintered in a shelter in the far north of Canada, but now Cook is on his way back and has set course for Copenhagen.

But it isn’t long before doubts arise.

Maybe Cook has not been as far north as he claims?

Amundsen does nothing but believe in his old friend from the Belgica expedition. He tells the newspapers that Cook's expedition was "planned as a sports affair," and that it will have no effect on his own expedition.

Tuesday, September 7, 1909

Stavanger Aftenblad 7.9.1909 / National Library of Norway.

Another surprising news headline.

“Stars and Stripes nailed to North Pole.” The message comes from another American, Robert Peary.

Peary also believes that he has been to the North Pole. On April 6, 1909, according to him, he stood there as the first to do so.

But can either of them prove it?

Who is telling the truth?

Perhaps Cook, perhaps Peary, perhaps neither of them.

For Amundsen, it changes things in any case.

According to him, Amundsen makes his decision the same day as the newspapers print the news of Robert Peary's expedition, September 7, 1909.

He decides that his expedition will have a new goal, which will be the pole still no one thinks they have reached, and the reason is financial. Amundsen later explains:

but in view of the altered circumstances, and the small prospect I now had of obtaining funds for my original plan, I considered it neither mean nor unfair to my supporters to strike a blow that would at once put the whole enterprise on its feet, retrieve the heavy expenses that the expedition had already incurred, and save the contributions from being wasted.

But great uncertainty remains. The crew receives only a preliminary message:

The expedition’s departure has had to be postponed for some months due to various delays. The departure will probably take place in July 1910.

- 1/1

An undated note, probably from September 7, 1909, written by Roald Amundsen to his brother and collaborator Leon Amundsen. Here Leon is instructed to inform Captain Thorvald Nilsen and the rest of the crew that the expedition has been postponed until July 1910. Photo: National Library of Norway.

On Thursday, September 8, Roald Amundsen boards the train to Copenhagen, his destination is the Hotel Phoenix where Frederick Cook is staying.

Officially, Amundsen has taken the trip to be part of honouring Cook. Twenty-five years later, Cook will relate that there was also talk of other things:

- 1/1

The equipment and dogs described are the same as originally ordered from the Royal Greenland Trading Department. The order was later expanded to include one hundred dogs. Photo: National Library of Norway.

Originally, Amundsen had planned to pick up dogs in Alaska on his way north. But in Copenhagen he writes a letter to Jens Daugaard-Jensen, Inspector of Greenland, that contains an order for dogs and equipment from there.

The order is written on Frederick Cook's letterhead.

When journalists ask, "Do these things with Peary and Cook have any effect on your business?"

Amundsen replies:

"They will not bring a trace of change in my plans."

Robert Falcon Scott (1868-1912) had extensive experience from the British Navy and had previously led an expedition to Antarctica. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Monday, September 13, 1909

The next big surprise comes from England, from Robert Falcon Scott.

The Briton who in 1901-1904 failed to reach the South Pole will now try again.

Scott plans to use horses, dogs, and motor sledges, in addition to the men pulling the sledges themselves.

Before he heads south, Scott also wants to go to Norway - to test the motor sledges, to meet Fridtjof Nansen and to get equipment.

Together with his wife, Kathleen, Scott comes to Norway in March 1910. During his stay, he is introduced to the Norwegian Tryggve Gran, whom he recruits to join the expedition. They then go to Fefor in Gudbrandsdalen to test the motor sledges and equipment.

While in Norway, Scott also wants to meet Roald Amundsen. Perhaps his work in the south can have a comparative value with the work Amundsen intends to do in the north?

Together with Tryggve Gran, he arranges a meeting with Roald Amundsen in his home Uranienborg in Svartskog. They drive out on the narrow, bad winter roads, but when they arrive, they are surprised.

Roald Amundsen is nowhere to be seen.

Just over an hour goes by without Roald Amundsen showing up. Eventually, Scott and Gran return to Oslo disappointed.

What could have been a historic meeting never materialized.Where Roald Amundsen was during these hours, and whether he avoided meeting Scott on purpose, no one knows.

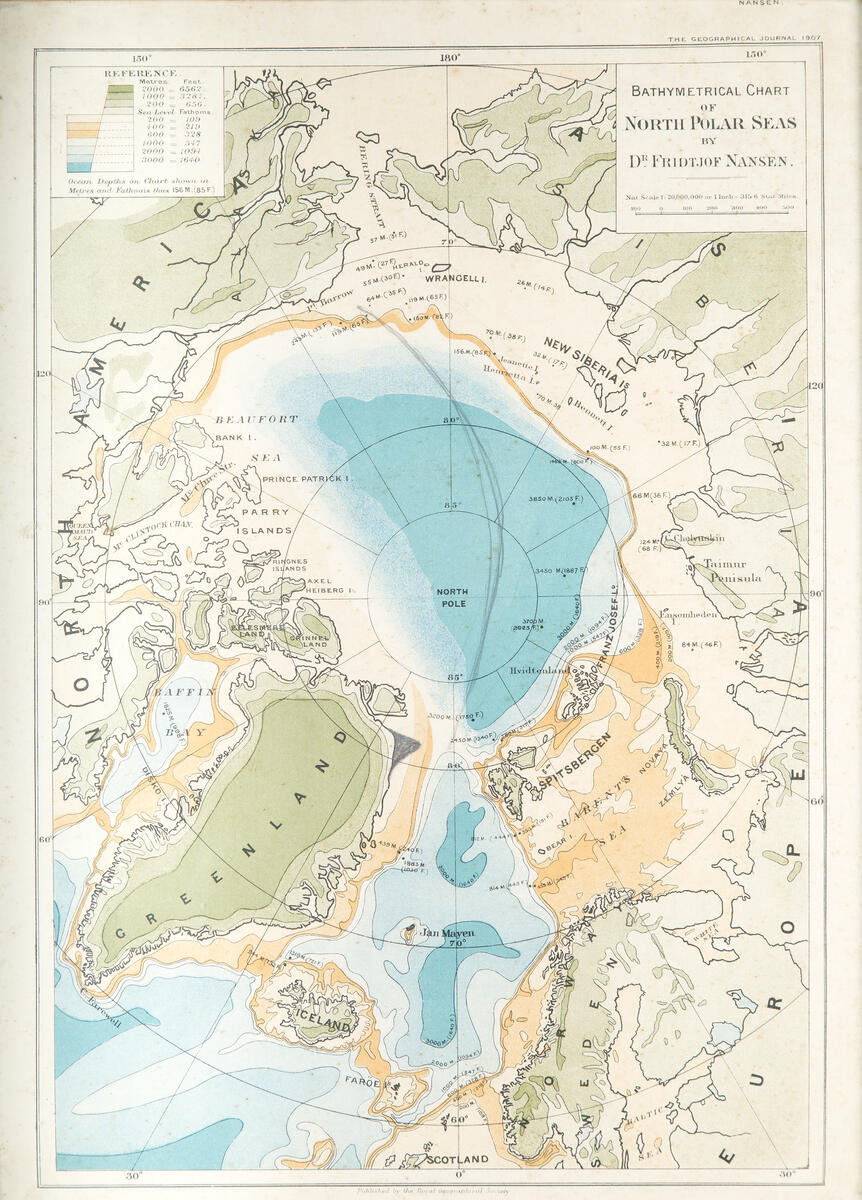

Nansen and Fram

As early as the autumn of 1907, Roald Amundsen went to Lysaker, outside Oslo, to the home of Fridtjof Nansen. This was the man Amundsen referred to as:

"the prophet, whom I always looked up to with awe."

Nansen was the nation's polar hero. He had led the first expedition across the Greenland ice sheet (1888) and the heroic Fram expedition across the Arctic Ocean (1893-1896). He was the scientist, the national hero, and the polar explorer, and he had plans for more expeditions. Among other things, he wanted to go to the South Pole, which would mean another long period away from his wife Eva.

when the da came and Amundsen was standing in the hall waiting for his answer, Eva could not disguise her anxiety. She was up in the bedroom and she heard Father’s slow tread above her head. She looked at him, eyebrows raised, as she came in, but all she said was: 'I know what it will be.' Father walked out again without a word and down the stairs to the hall, where he met another pair of anxious eyes. 'You shall have Fram,' he said.

Framheim

In the summer of 1910, Amundsen acquired another important element in reaching the South Pole. An overwintering hut.

Jørgen Stubberud and his brother Harald, born and raised in Svartskog, will be responsible for building the hut, together with several of the expedition members. Materials are purchased at Skedsmo Dampsag and Høvleri's outlet in Oslo.

The hut will be 8 metres long, 4 metres wide and 5 metres high under the apex.

The plan is to erect it on the grass by the flagpole outside Uranienborg and then dismantle it and load it aboard the Fram. That way, they can quickly rebuild it when they arrive in Antarctica.

But still, few people know where the hut will actually be used. Amundsen tells the journalists that the hut will be important on the journey across the Arctic Ocean.

In December 1909, Amundsen applies to the Norwegian Storting (Parliament) for more money, without informing them that the expedition has been given a southern sub-goal. He bases the application on his need for more money to pay for a larger crew for a longer period, but is rejected.

Although the Storting will give no more, both King Haakon and Queen Maud are enthusiastic about the expedition.

Thursday, June 2, 1910

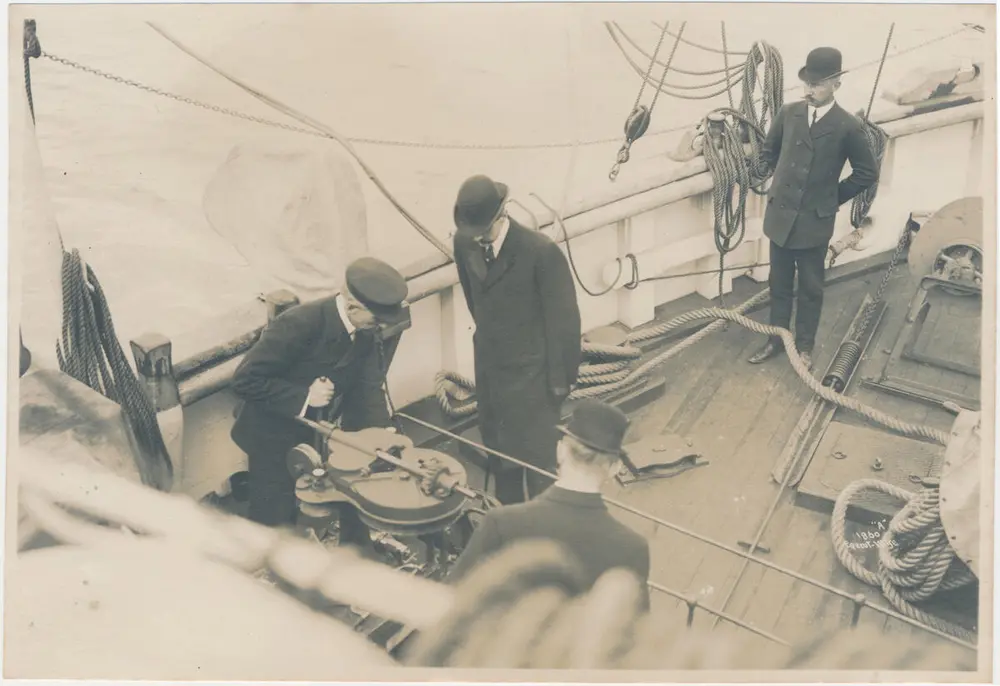

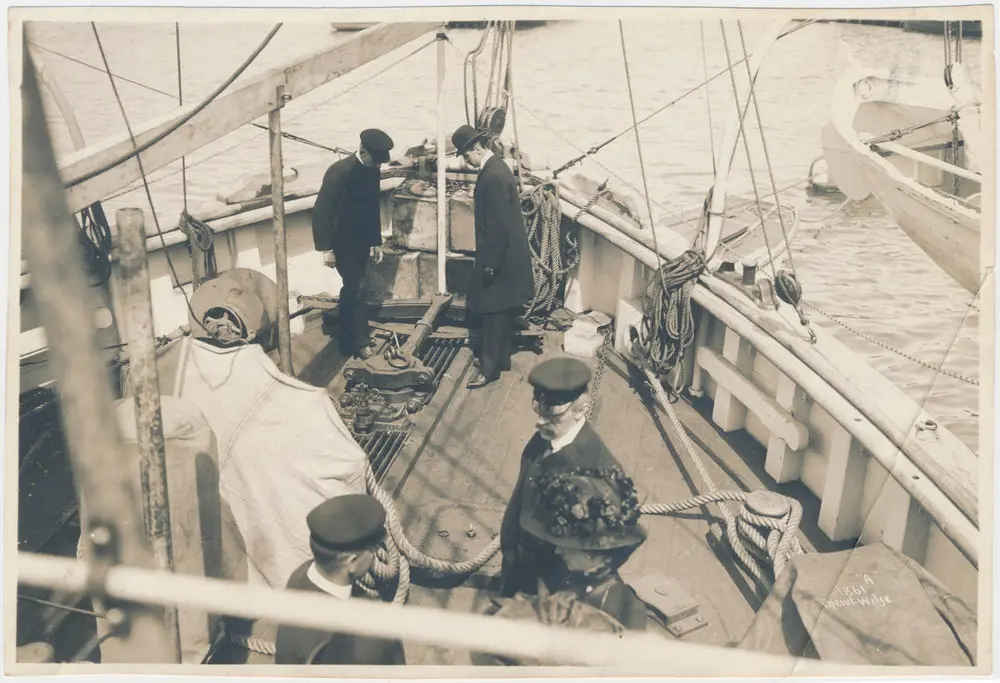

The royal couple arrive on board the Fram, having come straight from England where they attended the funeral of the queen’s father, King Edward VII. According to some, the queen looks worn out, and the king is also understood to be clearly moved and fraught.

On deck they are received by Amundsen. Fridtjof Nansen is also on board and standing behind are the crew in blue suits. One by one they are presented to the royal couple.

They gather in the large study to hear the King speak. The King emphasizes the value of science and says that wars these days are not fought with swords, but through pioneering scientific work. The expedition is presented with signed portraits of the king, queen and Crown Prince Olav, and a silver mug.

- 1/1

The portraits of the royal family were hung on board the Fram and were later also taken on the Maud expedition (1918-1925) and the voyage with the airship Norge across the Arctic Ocean (1926). Finally, they found a place on the wall in the blue living room in Roald Amundsen's House. Photo: Follo Museum, MiA.

Monday, June 6, 1910

At home at Uranienborg a farewell party is thrown. Moored just offshore is Fram and on board are the equipment and materials for Framheim. Ashore are Amundsen, the crew, and relatives and friends. In the garden are tables covered with flowers and cakes, and in the glasses there is sparkling wine. The gentlemen smoke cigars. Everyone has turned up to wish their loved ones a good trip north, ready to say goodbye for perhaps seven years.

One of the guests raises a glass and urges them to send good thoughts north in the coming years. Amundsen thanks them.

Roald's brother Leon comes running at the last minute, having punctured on the way when cycling over a broken horseshoe.

The horseshoe is nailed to the mast in the vestibule, for good luck.

Then the engine is started, the anchor is weighed and Fram begins the journey out into the fjord.

Only a few know where they are really going.

- 1/1

Fram moored off Roald Amundsen's home before departure in summer 1910. Photo: Norwegian Polar Institute / National Library of Norway