23. September 1924

Roald Amundsen is planning a long journey. An extensive lecture tour. America is the destination.

In his diary, which he has addressed to Kristine Elisabeth "Kiss" Bennett, he describes the plan:

"I am about to pack. I will have a lot of luggage, and I will pack it with Alaska in mind. I am going into exile, my little friend. The recent events have made me feel that I will always be uncomfortable here. Therefore, I will be on the other side of the Atlantic, until you call."

The situation is about to change. But Amundsen knows little about this as he begins his journey across the Atlantic.

He arrives in New York on October 6th and checks into his usual hotel in the city, the Waldorf Astoria.

American journalists write about his arrival, and the coincidences make everything change.

-

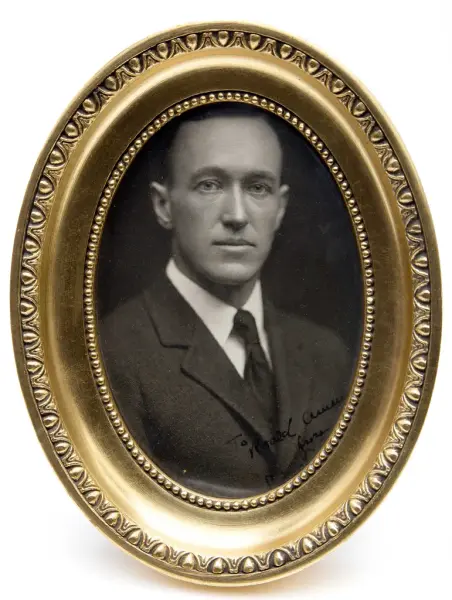

This framed picture of Ellsworth is today on Roald Amundsen's desk. Photo: Roald Amundsen's House, MiA

8. October 1924

Lincoln Ellsworth is 44 years old, restless, and wealthy. His real name was Linn, named after his uncle, but he took the name Lincoln.

He grew up with a wealthy father but only had 8 years with his mother before she died. Lincoln and his sister Clare were raised by their grandmother. His father, James William Ellsworth, had a lot of money but little time. The wealth mainly came from ownership in various mining companies.

Lincoln Ellsworth eventually sought out the world. He worked in railway construction in Alaska and Canada, in his father's mining industry, and he undertook several trips to South America. In October 1924, he had just returned from a trip to the Andes. He was actually on his way to Peru, but on the morning of October 8th, he quickly reads through the Herald Tribune. He notices a brief mention that Roald Amundsen has arrived in New York.

Ellsworth calls the Waldorf Astoria, asks to speak with Amundsen. They arrange to meet that afternoon.

In his diary, Amundsen later writes:

[...] Then came a man by the name of Lincoln Ellsworth – 42 years old, whom I met in Paris during the war. A strong, handsome figure. He would like to join in the flight. He has $20,000 of his own money, which he offers, but he also hopes to interest his father, who is very wealthy. Perhaps something will come of it."

They eat and talk. And they agree to meet again.

The next day, Amundsen completes an article about the plan up until now.

In it, he writes about the initial attempts, the pressure, and the finances. He writes about the failed attempts with the Maud-expedition and the pressure he felt to get this expedition off the ground.

«What in the world should I do? My country had granted me a sum far surpassing my highest expectations so I could not very well ask them for more. I would have to find another way out of it. Have you ever seen a rat caught in a trap? She is running round putting the nose in the air and trying to smell her way out. So did I. and I thought I had found the right way”.

The friendship with Lincoln Ellsworth develops quickly. On October 13th, Amundsen writes in his diary:

"Had lunch today with Lincoln Ellsworth, the one who so eagerly wants to be with me. I told him that he could work with all the money he could get and bring. He is brilliant. His father is said to be very wealthy and can easily pay for the entire expedition."

On November 6th, Amundsen meets both father and son for the first time. Later that day, Amundsen wrote in his diary:

Yesterday I was out visiting old Ellsworth. He must be "incredibly rich.

-

Photo: Hudson Library Historical Society

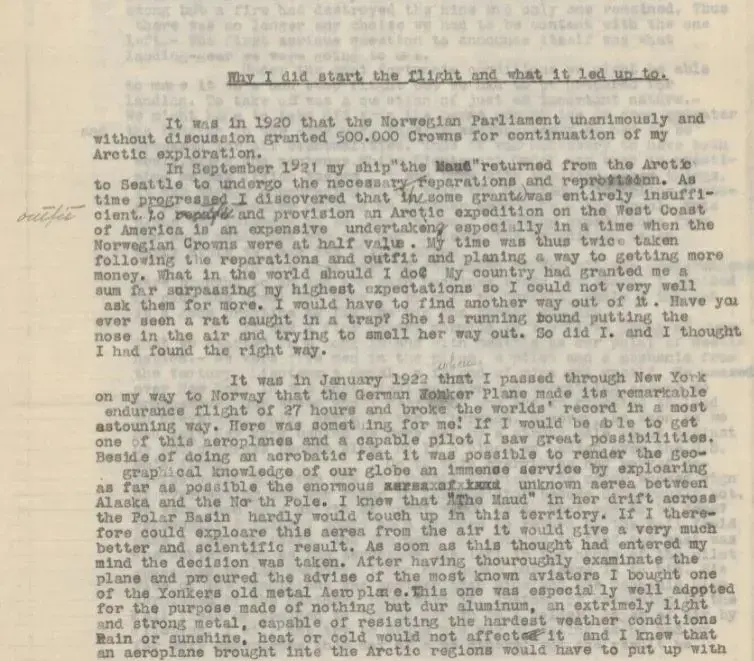

James William Ellsworth owned several buildings around the world, filling them with art, books, paintings, and sculptures. His collection included a Gutenberg Bible and one of the earliest self-portraits by Rembrandt.

In the 1920s, James William Ellsworth was not one to take large risks anymore. By 1925, he was 76 years old and recently widowed for the second time. He spent most of his time in America, but was also frequently at his historic and beautiful Italian property, Villa Palmieri, outside Florence.

9. November 1924

Amundsen is visiting James William Ellsworth again. Amundsen talks about the planned journey, the life he has lived, and what it’s like out there on the ice.

“What if I don’t want to help you? What will you do?” Ellsworth is said to have asked.

Amundsen replied, “The same thing I’ve always done, Mr. Ellsworth. I’ll manage somehow.”

According to Lincoln Ellsworth, it was this answer that convinced his father to contribute to the expedition.

That evening, Amundsen wrote in his diary:

I visited and spoke with old Ellsworth, who came this morning. He is now offering $80,000 as a guarantee for two machines, and with that, the matter is settled. Good heavens, how rich he must be. Paintings worth $75,000 each cover all the walls. Artifacts from 400 B.C. are both here and there. On the floor of one of the rooms, there’s a carpet from the 11th century!!

A few days later, the agreement is signed.

The only condition James William Ellsworth sets is that his son Lincoln must quit smoking. Lincoln agrees, but doesn't keep his word—he begins to smoke in secret.

As a token of gratitude, Amundsen brings a gift: the binoculars he used on the expedition through the Northwest Passage, to the South Pole, and through the Northeast Passage. He gives them to James William Ellsworth, who later passes them on to his son. Today, they are part of the collection at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

- 1/1

Amundsen used the binoculars on several expeditions, but gave them to James William Ellsworth. Photo: American Museum of Natural History.

21. November 1924

Now that the funding seems secured, Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, on behalf of the expedition, signs a new contract with Dornier for the delivery of two flying boats.

But things are not as certain as Amundsen believes.

Old Ellsworth begins to have doubts. He considers the plan too risky and wants his son Lincoln to withdraw. James William Ellsworth hires his lawyer to conduct a secret investigation into Amundsen’s background. He contacts people in both Norway and the United States. Although most report that Amundsen is a capable polar explorer but poor with money, James remains unconvinced.

Meanwhile, the friendship between Amundsen and Lincoln Ellsworth grows. They meet, dine, plan, and talk. Amundsen receives several gifts, including a $400 watch, which he notes in his diary. At the same time, old Ellsworth continues trying to pull his son out of the project.

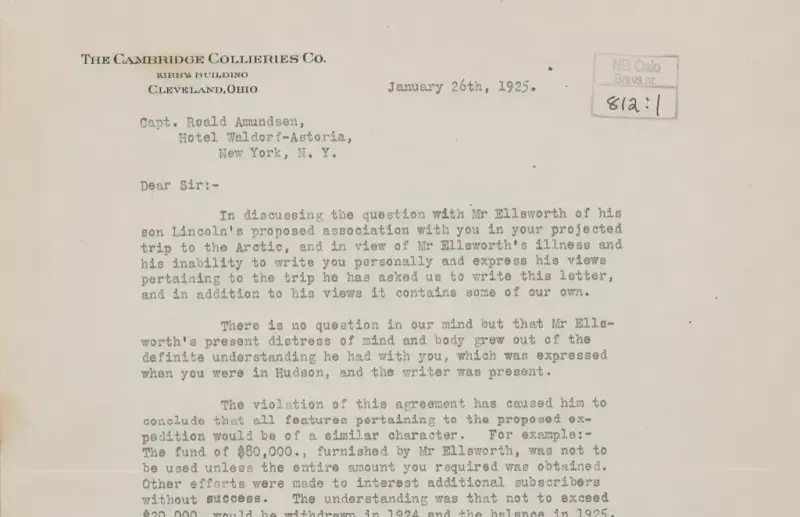

Amundsen receives several letters from James William Ellsworth and his lawyer during the autumn. Most concern finances and money matters, but on January 26, 1925, Amundsen receives a letter from Ellsworth’s lawyer stating that the old Ellsworth is ill and exhausted. The thought of what might happen is wearing him down. Unless his son withdraws from the plans, the old Ellsworth will suffer so much that it will “cause his death,” as the lawyer writes.

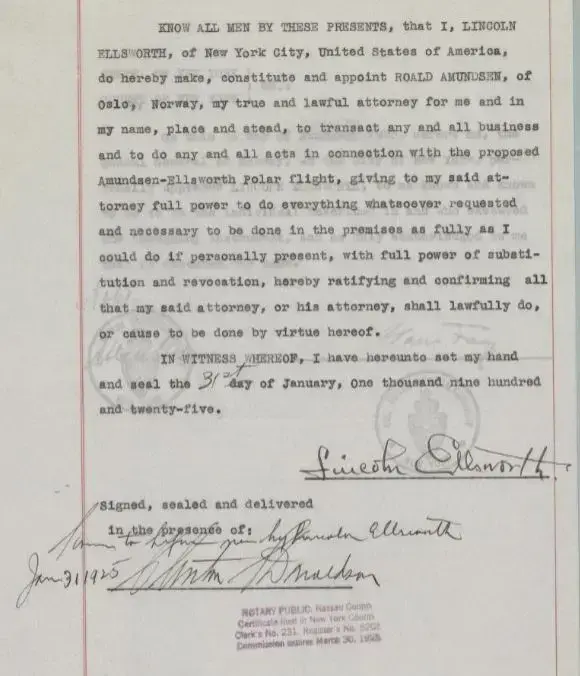

Five days later, on January 31, Lincoln Ellsworth signs the contract to take part in the expedition.

In March 1925, James writes a long letter to Lincoln. He reflects on their father-son relationship, accusing Lincoln of lacking respect and causing him nothing but worry and anxiety. He says he tries to fulfill his son's wishes, but:

the more I give you, the more independent you are against me, your father.

Lincoln turns to his sister Clare for support, but she too faces resistance from their father. If we are to believe Lincoln Ellsworth’s own words, the atmosphere in the family grew tense and the tone increasingly sharp as the departure approached. When Lincoln prepares to leave for Norway, he visits his father one final time.

When the time came for me to go, I went to Father to bid him good-bye, a most dismal experience. I had hoped that he might come to the boat, but he didn't. he had, of course, the excuse of ill-health, and the ordeal might have been too much for him.

Not long after, James William Ellsworth travels to his country estate, Villa Palmieri, outside Florence, Italy.

There, he contracts pneumonia, and shortly after, on June 2, 1925, he passes away.

He never learned whether his son survived the expedition.